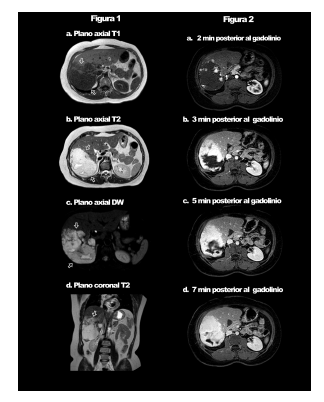

Mujer de 65 años a quien se le realizó una ecografía abdominal debido a dolor epigástrico postprandial de dos semanas de evolución, en la cual se observó extensa lesión heterogénea en lóbulo hepático derecho. Se decidió realizar una resonancia magnética (RM) de abdomen, antes y después de la inyección de gadolinio. La RM mostró lesión focal, ovalada, de contornos bien definidos, que comprometía la mayor parte del lóbulo hepático derecho, de 12.3 cm de diámetro longitudinal máximo (Fig. 1), con zonas de mayor intensidad central en las secuencias potenciadas para T2 (Fig. 1b y d) y restricción en la secuencia de difusión (Fig.1 c). Luego de la administración del gadolinio la secuencia potenciada en T1 con saturación grasa mostró un realce centrípeto, progresivo y de aspecto algodonoso (Fig. 2 a y d). Con estos hallazgos se diagnosticó hemangioma hepático gigante.

Los hemangiomas son los tumores benignos más comunes de este órgano. Se denominan gigantes cuando miden más de 4 cm, y representan solo el 10% de todos los hemangiomas, predominan en mujeres, tal vez por influencia hormonal en su crecimiento. En general son asintomáticos y su hallazgo es incidental, pero pueden presentar síntomas por compresión de órganos adyacentes. El diagnóstico se logra por medio de TC o RM contrastadas, donde el patrón de captación del medio de contraste, centrípeto, lo diferencia de otras lesiones hepáticas focales (Fig. 2 a-d).

Jairo Hernández Pinzón, Kelly Ruiz, Nicolás Rocatagliata, Germán Espil, Nebil Larrañaga, Shigeru Kozima

Departamento de Imágenes, Centro de Educación Médica e Investigaciones Clínicas (CEMIC),

Buenos Aires, Argentina

e-mail: jahernandezpinzon@gmail.com

Bibliografía

1. Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med 2012; 14: 10-26.

2. Kalsner L, Chamberlain SJ. Prader-Willi, Angelman, and 15q11-q13 duplication syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am 2015; 62: 587-606.

3. Dagli AI, Williams CA. Angelman Syndrome. En: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1144; consultado mayo 2017

4. Margolis SS, Sell GL, Zbinden MA, Bird LM. Angelman syndrome. Neurotherapeutics 2015; 12: 641-50.

5. Finucane BM, Lusk L, Arkilo D, et al. 15q Duplication syndrome and related disorders. En: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK367946; consultado mayo 2017

6. Horsthemke B, Wagstaff J. Mechanisms of imprinting of the Prader-Willi/Angelman region. Am J Med Genet Part A 2008; 146: 2041-52.

7. Dawson AJ, Cox J, Hovanes K, Spriggs E. PWS/AS MS-MLPA confirms maternal origin of 15q11.2 microduplication. Case Rep Genet 2015; 2015: 1-3.

8. Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Talebizadeh Z, Butler MG. Microarray analysis of gene/transcript expression in Prader-Willi syndrome: deletion versus UPD. J Med Genet 2003; 40: 568-74.

9. Perk J, Makedonski K, Lande L, Cedar H, Razin A, Shemer R. The imprinting mechanism of the Prader-Willi/Angelman regional control center. EMBO J 2002; 21: 5807-14.

10. Ramsden SC, Clayton-Smith J, Birch R, Buiting K. Practice guidelines for the molecular analysis of Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. BMC Med Genet 2010; 70: 1-11.

11. Libov A, Maino M. D. Prader-Willi Syndrome. J Am Optom Assoc 1994; 65: 355-9.

12. Tan WH, Bacino CA, Skinner SA, et al. Angelman syndrome: Mutations influence features in early childhood. Am J Med Genet 2011; 155: 81-90.

13. Depienne C, Moreno-De-Luca D, Heron D, et al. Screening for genomic rearrangements and methylation abnormalities of the 15q11-q13 region in autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 66: 349-59.

14. Chai JH, Locke DP, Greally JM, et al. Identification of four highly conserved genes between breakpoint hotspots BP1 and BP2 of the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndromes deletion region that have undergone evolutionary transposition mediated by flanking duplicons. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 73: 898-925.

15. Buiting K, Cassidy SB, Driscoll DJ, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Prader-Willi Syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2014; 22.

16. Nygren AOH, Ameziane N, Duarte HMB, et al. Methylation-specific MLPA (MS-MLPA): simultaneous detection of CpG methylation and copy number changes of up to 40 sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2005; 33: 1-9.

17. Procter M, Chou LS, Tang W, Jama M, Mao R. Molecular diagnosis of Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes by methylation-specific melting analysis and methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Clin Chem 2006; 52: 1276-83.

18. Branham MT, Marzese DM, Laurito SR, et al. Methylation profile of triple-negative breast carcinomas. Oncogenesis 2012; 1: 1-7.

19. Goldstone AP, Patterson M, Kalingag N, et al. Fasting and postprandial hyperghrelinemia in Prader-Willi syndrome Is partially explained by hypoinsulinemia, and is not due to peptide YY 3-36 deficiency or seen in hypothalamic obesity due to craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90 : 2681-90.

20. Takano K, Lyons M, Moyes C, Jones J, Schwartz C. Two percent of patients suspected of having Angelman syndrome have TCF4 mutations. Clin Genet 2010; 78: 282-8.

21. Cassidy SB, Dykens E, Williams CA. Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes: sister imprinted disorders. Am J Med Genet 2000; 97: 136-46.

22. Robinson WP, Christian SL, Kuchinka BD, et al. Somatic segregation errors predominantly contribute to the gain or loss of a paternal chromosome leading to uniparental disomy for chromosome 15. Clin Genet 2000; 57: 349-58.

23. Varela MC, Kok F, Otto PA, Koiffmann CP. Phenotypic variability in Angelman syndrome: comparison among different deletion classes and between deletion and UPD subjects. Eur J Hum Genet 2004;12 : 987-92.

24. Wandstrat AE, Leana-Cox J, Jenkins L, Schwartz S. Molecular cytogenetic evidence for a common breakpoint in the largest inverted duplications of chromosome 15. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 925-36.

25. Henkhaus RS, Kim S-J, Kimonis VE, et al. Methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification and identification of deletion genetic subtypes in Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2012; 16: 178-86.