GUILLERMO D. MAZZOLINI, MARIANA MALVICINI

Laboratorio de Terapia Génica, Instituto de Investigaciones en Medicina Traslacional (IIMT),

Facultad de Ciencias Biomédicas, CONICET- Universidad Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Abstract Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second cause of cancer-related death in the world and is

the main cause of death in cirrhotic patients. Unfortunately, the incidence of HCC has grown significantly in the last decade. Curative treatments such as surgery, liver transplantation or percutaneous ablation can only be applied in less than 30% of cases. The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib is the first line therapy for advanced HCC. Regorafenib is the standard of care for second-line patients. However, novel and more specific potent therapeutic approaches for advanced HCC are still needed. The liver constitutes a unique immunological microenvironment, although anti-tumor immunity seems to be feasible with the use of checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab. Efficacy may be further increased by combining checkpoint inhibitors or by applying loco-regional treatments. The success of immune checkpoint blockade has renewed interest in immunotherapy in HCC.

Key words: hepatocellular carcinoma, immunostimulatory monoclonal antibodies, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen

4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death 1 ligand (PD1-L), tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Resumen Anticuerpos monoclonales inmunoestimulantes para el tratamiento del hepatocarcinoma.

Avances y perspectivas. El hepatocarcinoma (HCC) es la segunda causa de muerte relacionada con el cáncer en el mundo y es la principal causa de muerte en pacientes cirróticos. Desafortunadamente, la incidencia de HCC ha crecido significativamente en la última década. Los tratamientos curativos como la cirugía, el trasplante de hígado o la ablación solo pueden aplicarse en menos del 30% de los casos. El sorafenib es el tratamiento de primera línea para el HCC avanzado, mientras que el regorafenib se reserva como segunda línea. Sin embargo, todavía son necesarios nuevos enfoques terapéuticos potentes y más específicos para el HCC avanzado. El hígado constituye un microambiente inmunológico único, aunque la inmunidad antitumoral parece ser factible mediante el uso de inhibidores de punto de control como nivolumab. La eficacia puede aumentarse adicionalmente combinando inhibidores de puntos de control inmunitario o aplicando tratamientos loco-regionales. En este sentido, el éxito del uso de anticuerpos monoclonales, que bloquean el control inmunitario, ha renovado el interés en la inmunoterapia para el HCC.

Palabras clave: hepatocarcinoma, anticuerpos inmunoestimuladores, antígeno-4 asociado al linfocito T citotóxico (CTLA-4), ligando de la molécula de muerte celular programada 1 (PD1-L), linfocitos infiltrantes tumorales

Received: 29-IX-2017 Accepted: 12-XII-2017

Postal address: Guillermo Mazzolini, Laboratorio de Terapia Génica, Instituto de Investigaciones en Medicina Traslacional, Facultad de Ciencias Biomédicas, CONICET-Universidad Austral, Av. Pte. Perón 1500, 1629 Derqui-Pilar, Buenos Aires, Argentina

e-mail: gmazzoli@austral.edu.ar

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second cause of cancer-related death worldwide and its incidence is steadily increasing1. HCC primarily develops from cirrhosis, and most patients are infected with hepatitis C or B virus2. Non-viral HCC etiologies, such as diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are growing in frequency particularly in Western European patients3. Unfortunately, more than 750 000 cases are diagnosed each year and the majority of them are at advanced stages when curative treatments are very difficult to apply1, 4. For advanced HCC, the first line systemic therapy option is the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib, which offers an increase in overall survival from 7.9 months to 10.7 months when compared to placebo5. Although a large majority of patients progress on sorafenib, treatment with regorafenib in second line, a similar molecule in terms of mechanisms of antitumoral activity and side effects, improved overall survival by 2.8 months vs. placebo6. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more effective options for patients with advanced HCC.

Liver immunotolerance

It is well known that cancer is a complex and multifactorial disease; tumor cells have the ability to release a number of factors that can assist their capacity to grow and metastasize7. One of the most important characteristics of tumors is their capacity to evade immune surveillance8, 9. Preclinical and clinical data demonstrated that the intratumoral microenvironment is highly immunosuppressive and there is a poor effector T cell response in advanced HCC10. Independently of the causative disease, HCC can be considered as an inflammatory tumor composed by different types of immune cells that tilt the balance toward a state of immunotolerance8. This immunosuppressive microenvironment is characterized, at least in part, by the presence of CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells (Tregs), type 2 macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, tumor associated fibroblasts, Kupffer cells, just to mention a few11. It has been previously reported that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes correlate with improved survival in patients with HCC12. Thus, it is reasonable to consider immunotherapy as a rational therapeutic tool for patients with advanced or progressed HCC. The main goal of the majority of immunotherapy approaches is to generate a potent specific cytotoxic T cell response against cancer cells. The list of strategies applied so far include tumor vaccines, adoptive T cell therapy (including CAR-T cells), immune-gene therapy with oncolytic vectors, dendritic cells-based vaccines and, more recently, the use of immunostimulatory monoclonal antibodies, particularly the immune checkpoint inhibitors13. Checkpoint blockade has become a major focus in the immune-based therapy of HCC. The main concept involves inhibition of regulatory cell surface molecules, which normally inhibit T-cell activation.

Immune checkpoint antibody therapy for HCC

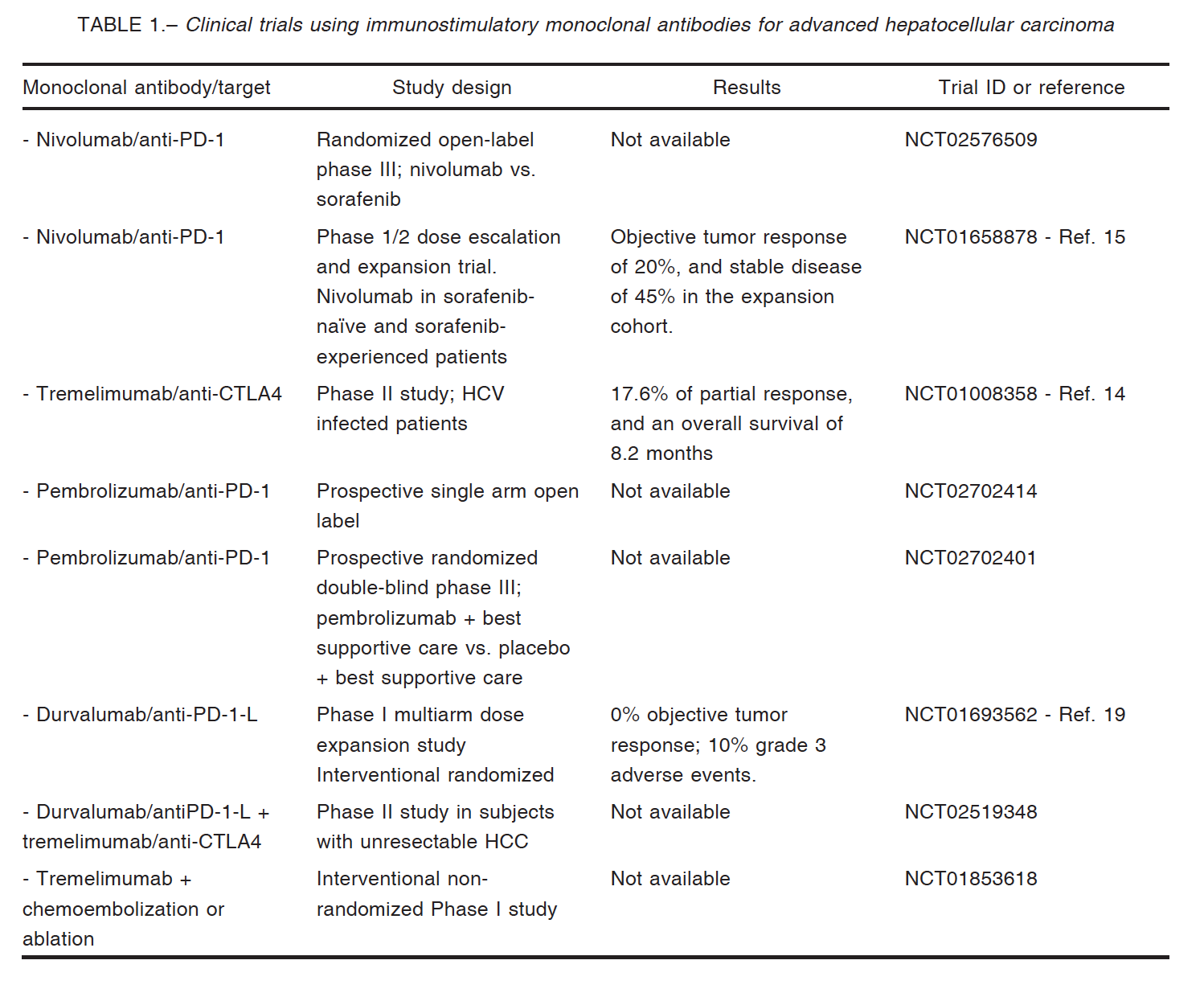

Sangro et al14 demonstrated in a pilot study that the Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor tremelimumab has promising antitumoral activity in patients with advanced HCC with hepatitis C virus infection. Twenty patients were treated with tremelimumab resulting in 17.6% of partial response and an overall survival of 8.2 months. More recently, a phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial (CheckMate 040) evaluated nivolumab in sorafenib-naïve as well as in sorafenib-experienced HCC. Nivolumab is a fully human (IgG4) monoclonal antibody

inhibitor of the programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor that restores T-cell–mediated antitumor activity15. Nivolumab has demonstrated clinical benefit in melanoma, refractory non-small cell lung cancer, advanced renal cell carcinoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and urothelial carcinoma16. In the CheckMate 040 study, 262 patients were enrolled and the primary end point was safety and tolerability (escalation phase) and overall response rate (expansion phase). As a result, in sorafenib-experienced patients with or without chronic viral hepatitis, nivolumab demonstrated a long-term survival and durable objective responses; in addition, safety profiles of nivolumab were similar to what has been observed in other tumor types; importantly, hepatic safety events were also manageable. Of note, clinical responses occurred irrespective of PD-L1 expression on cancer cells. A phase 3 study evaluating nivolumab in systemic treatment–naïve patients with advanced HCC is being carried out (CheckMate 459, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02576509) and will be of paramount importance if the study confirms the results obtained with nivolumab in phase 1/2 trial.

These promising results open the possibility for combinations using checkpoint inhibitors such as tremelimumab with other strategies, for example loco-regional treatments (local ablation or trans-arterial chemoembolization) which release tumor antigens into the bloodstream. Duffy et al reported promising results in terms of overall survival and objective responses; interestingly, patients showing increased intratumoral levels of CD8+ T cells, reached better clinical outcome17.

Nivolumab showed similar immune-related adverse events in HCC patients in comparison with other types of tumors; no serious liver dysfunction or autoimmune disease was observed17. El-Khoueiry et al reported that in the dose-escalation phase of the CheckMate040 trial only one of 48 patients who received nivolumab at the dose of 3 mg/kg discontinued therapy due to elevated liver transaminases. One patient showed grade 4 toxicity because of increased lipase, and the only grade 3 events were elevated AST levels in 5 patients and elevated ALT levels in 4 more patients15. In the dose expansion phase (n = 214) HCC patients were treated with 3 mg/kg; in this phase, 40 (19%) patients presented grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events15 (Table 1).

Recently, Rammohan et al reported the first case of metastatic HCC following liver transplantation that responded to the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab, after the failure of sorafenib therapy18. The patient showed complete radiological response and remains well with no evidence of tumor recurrence or organ rejection19.

In conclusion, the liver constitutes a unique immunological microenvironment, with multiple immunotolerant mechanisms that favor HCC development. Re-establishing anti-tumor immunity seems to be feasible and the results with checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab are promising; however, confirmation of the efficacy of nivolumab in the phase 3 clinical trial is pending. It is also important to identify predictive immunological biomarkers to help hepatologists in therapeutic decision-making. Efficacy may be further increased by combining checkpoint inhibitors (e.g. nivolumab and ipilimumab), though with increased toxicity, or by applying loco-regional treatments.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported in part by Instituto Nacional del Cáncer (Asistencia financiera para proyectos de investigación en cáncer de origen nacional III).

References

1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: E359-86.

2. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, London WT. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: an emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clin Liver Dis 2015; 19: 223-38.

3. European Association for The Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012; 56: 908-43.

4. Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 835-53.

5. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 378-90.

6. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 56-66.

7. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144: 646-74.

8. Mazzolini G, Ochoa MC, Morales-Kastresana A, Sanmamed MF, Melero I. The liver, liver metastasis and liver cancer: a special case for immunotherapy with cytokines and immunostimulatory monoclonal antibodies. Immunotherapy 2012; 4: 1081-5.

9. Matar P, Alaniz L, Rozados V, et al. Immunotherapy for liver tumors: present status and future prospects. J Biomed Sci 2009; 16: 30.

10. Willimsky G, Schmidt K, Loddenkemper C, Gellermann J, Blankenstein T. Virus-induced hepatocellular carcinomas cause antigen-specific local tolerance. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 1032-43.

11. Makarova-Rusher OV, Medina-Echeverz J, Duffy AG, Greten TF. The yin and yang of evasion and immune activation in HCC. J Hepatol 2015; 62: 1420-9.

12. Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, et al. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2006; 10: 99-111.

13. Prieto J, Melero I, Sangro B. Immunological landscape and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 681-700.

14. Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2013; 59: 81-8.

15. El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 2492-502.

16. Wang X, Bao Z, Zhang X, et al. Effectiveness and safety of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in the treatment of solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 59901-14.

17. Duffy AG, Ulahannan SV, Makorova-Rusher O, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017; 66: 545-51.

18. Rammohan A, Reddy MS, Farouk M, Vargese J, Rela M. Pembrolizumab for metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma following live donor liver transplantation: the silver bullet? Hepatology 2017. doi: 10.1002/hep.29575. [Epub ahead of print]

19. Segal NH, Hamid O, HwuW, et al. A phase i multi-arm dose-expansion study of the anti-programmed cell death-ligand-1 (PD-L1) antibody medi4736: preliminary data. Ann Oncol 2014; 25 (Suppl 4): iv365.

– – – –

LA TAPA

Daniela Kantor, Cañadón, 2017

Acrílico sobre tela. 31.5 × 49.5 cm

Daniela Kantor es diseñadora gráfica (FADU- UBA), historietista, ilustradora y pintora. Desde 2014 es docente en la materia Ilustración, cátedra Roldán, FADU, y da talleres para niños (Filbita 2017, taller de comics librerías Matilda-Tigre, taller de historietas CCK, etc.) Estudió con el maestro Alberto Breccia dibujo de historieta y con Carlos Gorriarena realizó el Curso de color. Asistió al Taller de acuarela y pastel de Carlos Nine y realizó clínicas de pintura con Mariano Sapia y Tulio de Sagastizábal. Además de ilustrar muchos libros para niños y adolescentes (Editoriales Troquel, Abran Cancha, Puerto de Palos, Santillana, etc.), es parte de la revista de historietas El tripero, publica en revistas (Barcelona, Zona de obras, Crisis, suplemento Ñ, entre otras). Publicó su primera novela gráfica: Mujer primeriza (2014). Su proyecto de segundo libro de historietas Naturalella obtuvo la primera mención del Premio Nueva Historieta Argentina (2016) y fue publicado en parte en Dis-tinta, el compilado de Liniers y Martín Pérez (Ed. Sudamericana, 2016).

Fuentes: www.danielakantor.com; www.kantorconk.blogspot.com; www.danikantor.portfoliobox.net